The Court of Oyer and Terminer held witch trials on four occasions during 1692, with most sittings spanning a period of several days. The court could conduct multiple trials over the course of each convening because the proceedings moved at a dazzlingly fast pace, often lasting little more than an hour. By 1693 the trials were dwindling in intensity and all those accused had been pardoned and released from prison. Finally in 1697, the Massachusetts General Court declared a day of fasting for the victims of the Salem witch trials and they were later deemed unlawful.

Posted on Oct 29, 2012, by Lyonette Louis-JacquesJanuary 20, 1692- Betty Parris, Reverend Parris’ nine year old daughter, falls ill. Soon, other girls in Salem Village are likewise “afflicted.” Mid-February- D. William Griggs, village physician, examines the afflicted girls and pronounces their alarming behavior to be caused by bewitchment. February 25- Following the directions given to them by their neighbor Mary Sibley.

The law of the Salem Witch Trials is a fascinating mix of biblical passages and colonial statutes. According to Mark Podvia (see Timeline, PDF), the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony adopted the following statute in 1641: “If any man or woman be a WITCH, that is, hath or consulteth with a familiar spirit, they shall be put to death. Exod. 22. 18. Levit. 20. 27. Deut. 18. 10. 11.” The statute encompasses passages from the Bible written circa 700 B.C. Exodus states: “Thou shall not suffer a witch to live.” Leviticus prescribes the punishment. Witches and wizards “shall surely be put to death: they shall stone them with stones: their blood shall be upon them.” And Deuteronomy states: “There shall not be found among you any one that maketh his son or his daughter to pass through the fire, or that useth divination, or an observer of times, or an enchanter, or a witch. Or a charmer, or a consulter with familiar spirits, or a wizard, or a necromancer.”

In Salem, the accusers and alleged victims came from a small group of girls aged nine to 19, including Betty Parris and Abigail Williams. In January 1692, Betty and Abigail had strange fits. Rumors spread through the village attributing the fits to the devil and the work of his evil hands. The accusers claimed the witchcraft came mostly from women, with the notable exception of four-year old Dorcas Good.

The colony created the Court of Oyer and Terminer especially for the witchcraft trials. The law did not then use the principle of “innocent until proven guilty” – if you made it to trial, the law presumed guilt. If the colony imprisoned you, you had to pay for your stay. Courts relied on three kinds of evidence: 1) confession, 2) testimony of two eyewitnesses to acts of witchcraft, or 3) spectral evidence (when the afflicted girls were having their fits, they would interact with an unseen assailant – the apparition of the witch tormenting them). According to Wendel Craker, no court ever convicted an accused of witchcraft on the basis of spectral evidence alone, but other forms of evidence were needed to corroborate the charge of witchcraft. Courts allowed “causal relationship” evidence, for example, to prove that the accused possessed or controlled an afflicted girl. Prior conflicts, bad acts by the accused, possession of materials used in spells, greater than average strength, and witch’s marks also counted as evidence of witchcraft. If the accused was female, a jury of women examined her body for “witch’s marks” which supposedly showed that a familiar had bitten or fed on the accused. Other evidence included the “touching test” (afficted girls tortured by fits became calm after touching the accused). Courts could not base convictions on confessions obtained through torture unless the accused reaffirmed the confession afterward, but if the accused recanted the confession, authorities usually tortured the accused further to obtain the confession again. If you recited the Lord’s Prayer, you were not a witch. The colony did not burn witches, it hanged them.

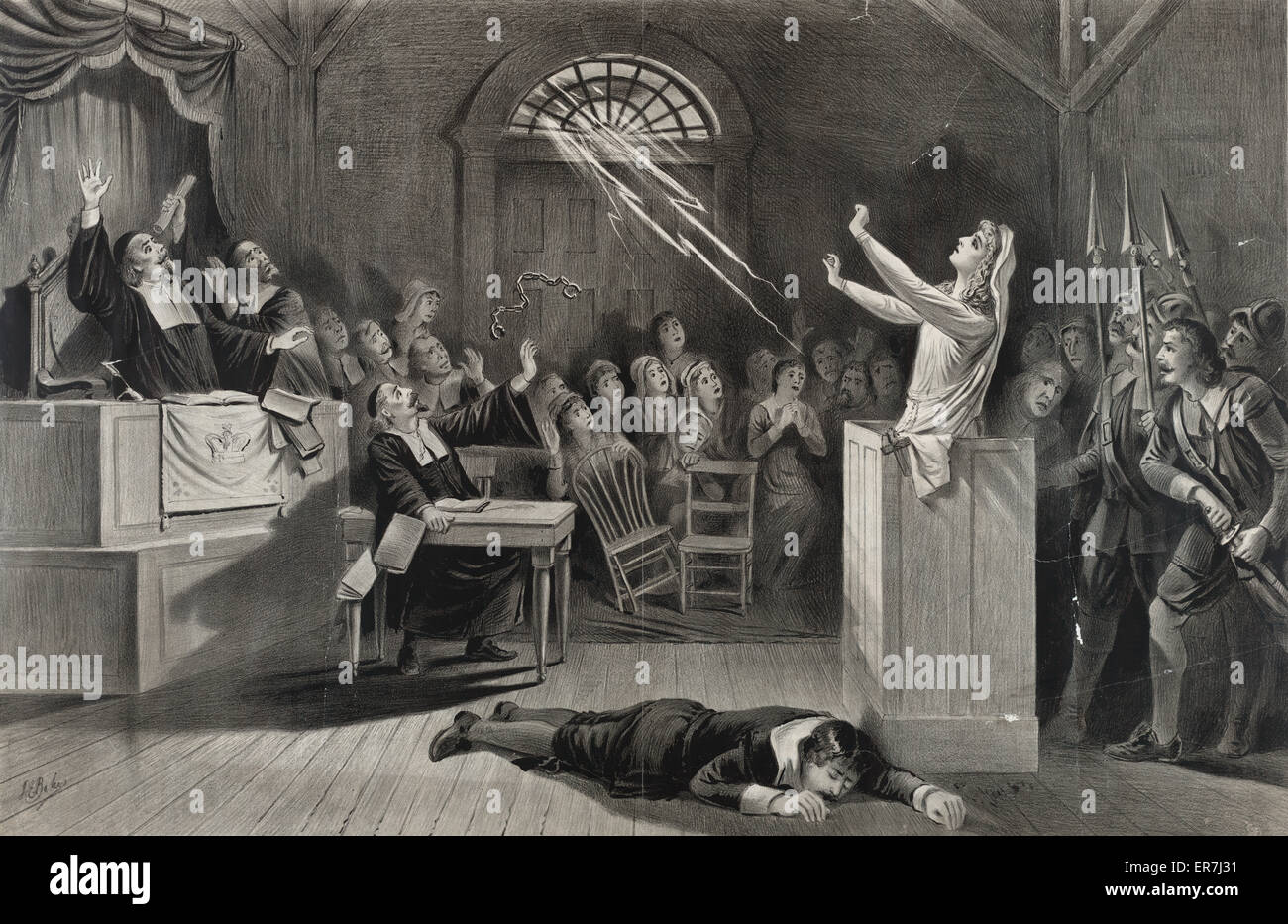

- Scene in the courtroom during The Salem witch trials of 1692. From The History of Our Country, published 1899 witch house in salem, massachusetts - salem witch trials stock pictures, royalty-free photos & images.

- The trials resulted in the executions of twenty people, most of whom were women. The central figure in this 1876 illustration of the courtroom in the Salem witch trials is usually identified as Mary Walcott, one of the accusers.

The Salem Witch Trials divided the community. Neighbor testified against neighbor. Children against parents. Husband against wife. Children died in prisons. Familes were destroyed. Churches removed from their congregations some of the persons accused of witchcraft. After the Court of Oyer and Terminer was dissolved, the Superior Court of Judicature took over the witchcraft cases. They disallowed spectral evidence. Most accusations of witchcraft then resulted in acquittals. An essay by Increase Mather, a prominent minister, may have helped stop the witch trials craze in Salem.

Researching the Salem Witch Trials is easier than it used to be. Most of the primary source materials (statutes, transcripts of court records, contemporary accounts) are available electronically. Useful databases include HeinOnline Legal Classics Library (see Trials for Witchcraft before the Special Court of Oyer and Terminer, Salem, Massachusetts, 1692; The Salem Witchcraft (Clair, Henry St., 1840); and “Witch Trials,” 1 Curious Cases and Amusing Actions at Law including Some Trials of Witches in the Seventeenth Century (1916) ), HeinOnline World Trials Library, HeinOnline Law Journal Library (also JSTOR, America: History & Life, Google Scholar, and the LexisNexis and Westlaw journal databases), Gale Encyclopedia of American Law (“Salem Witch Trials“), Google Books, Hathi Trust, and the Internet Archive. For books and articles on the Salem Witch Trials and witchcraft and the law generally, Library of Congress subject headings include:

- Trials (Witchcraft) — History

- Trials (Witchcraft) — Massachusetts — Salem

- Witch hunting — Massachusetts — Salem

- Witchcraft — Massachusetts — Salem — History — 17th century

- Witchcraft — New England

- Witches — Crimes against

- Salem Witch Trials: Documentary Archive & Transcription Project (University of Virginia)(includes online searchable text of the transcription of court records as published in Boyer/Nissenbaum’s The Salem Witchcraft Papers, revised 2011, and e-versions of contemporary books)

- Famous American Trials: Salem Witch Trials, 1692 (Prof. Douglas O. Linder, University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School)

Adams, Gretchen A. The Specter of Salem: Remembering the Witch Trials in Nineteenth-Century America (University of Chicago Press, BF1576.A33 2008).

Boyer, Paul & Stephen Nissenbaum, eds. The Salem Witchcraft Papers: Verbatim Transcripts of the Legal Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Outbreak of 1692 (Da Capo Press, XXKFM2478.8.W5S240 1977)(digital edition, revised and augmented, 2011). 3v.

___________________________. Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft (Harvard University Press, BF1576.B79 1974). See especially pages 1-59.

___________________________, eds. Salem Village Witchcraft: A Documentary Record of Local Conflict in Colonial New England (Wadsworth Pub. Co., KA653.B75 1972 LawAnxS).

Brown, David C. “The Case of Giles Corey.” EIHC (Essex Institute Historical Collections, F72.E7E81) 121 (1985): 282-299.

___________. “The Forfeitures of Salem, 1692.” The William and Mary Quarterly 50 (1993): 85-111.

Burns, William E. Witch Hunts in Europe and America: An Encyclopedia (Greenwood Press, BF1584.E9B87 2003). Includes a Chronology (1307-1793), “Salem Witch Trials” at pages 257-261, and a bibliography at pages 333-347.

Burr, George Lincoln. Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases, 1648-1706 (Barnes & Noble, BF1573.B6901 1963).

Calef, Robert. More Wonders of the Invisible World (1700).

Craker, Wendel D. “Spectral Evidence, Non-Spectral Acts of Witchcraft, and Confession at Salem in 1692. ” Historical Journal 40 (1997): 331-358.

Demos, John. Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England (Oxford University Press, BF1576.D38 1982).

Francis, Richard. Judge Sewall’s Apology: The Salem Witch Trials and the Forming of the American Conscience (Fourth Estate, F67.S525 2005).

Godbeer, Richard. The Salem Witch Hunt: A Brief History with Documents (Bedford/St. Martin’s, XXKFM2478.8.W5G63 2011).

Hansen, Chadwick. Witchcraft at Salem (G. Braziller, BF1576.H25 1969).

Hill, Frances. The Salem Witch Trials Reader (Da Capo Press, BF1576.H55 2000).

Hoffer, Peter Charles. The Salem Witchcraft Trials: A Legal History (University Press of Kansas, XXKFM2478.8.W5H645 1997)(Landmark Law Cases & American Society).

______________. The Devil’s Disciples: Makers of the Salem Witchcraft Trials (Johns Hopkins University Press, XXKFM2478.8.W5H646 1996).

Salem Witch Trial Courtroom

Karlsen, Carol F. The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England (Norton, BF1576.K370 1987).

Le Beau, Bryan F. The Story of the Salem Witch Trials: “We Walked in Clouds and We Could Not See Our Way” (Prentice Hall, 2d ed., XXKFM2478.8.W5L43 2010)(DLL has 1998).

Levin, David. What Happened in Salem? (2d ed. Harcourt, Brace & Co. BF1575.L40 1960) (Documents Pertaining to the Seventeenth-Century Witchcraft Trials). Compiles trial evidence documents, contemporary comments, and legal redress.

Mather, Cotton. The Wonders of the Invisible World: Being an Account of the Tryals of Several Witches Lately Executed in New England, and Of Several Remarkable Curiosities Therein Occurring (1693) .

Mather, Increase. Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits Personating Men, Witchcrafts, Infallible Proofs of Guilt in Such As Are Accused with That Crime (1693).

Nevins, Winfield S. Witchcraft in Salem Village in 1692 (North Shore Pub. Co., BF1576.N5 1892).

Norton, Mary Beth. In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692 (BF1575.N67 2002)(legal analysis, with appendixes).

Powers, Edwin. Crime and Punishment in Early Massachusetts, 1620-1692 A Documentary History (Beacon Press, KB4537.P39C8 1966 LawAnxN).

Rosenthal, Bernard ed. Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt (Cambridge University Press, XXKFM2478.8.W5R43 2009)(includes Richard B. Trask, “Legal Procedures Used During the Salem Witch Trials and a Brief History of the Published Versions of the Records” at pages 44-63).

Ross, Lawrence J., Mark W. Podvia, & Karen Wahl. The Law of the Salem Witch Trials. American Association of Law Library, Annual Meeting, Boston, Massachusetts, July 23, 2012 (AALL2go – password needed to access .mp3 and program handout).

Starkey, Marion. The Devil in Massachusetts: A Modern Inquiry into the Salem Witch Trials (A.A. Knopf, XXKFM2478.8.W5S73 1949).

Upham, Charles W. Salem Witchcraft: with an Account of Salem Village and a History of Witchcraft and Opinions on Kindred Subjects(Wiggin & Lunt, 1867). 2v.

Weisman, Richard. Witchcraft, Magic, and Religion in 17th-Century Massachusetts (The University of Massachusetts Press, XXKFM2478.8.W5W4440 1984). Includes a chapter on “The Crime of Witchcraft in Massachusetts Bay Historical Background and Pattern of Prosecution.” Appendixes includes lists of legal actions against witchcraft prior to the Salem prosecutions, Massachusetts Bay witchcraft defamation suits, persons accused of witchcraft in Salem, confessors, allegations of ordinary witchcrafts by case, afflicted persons.

Young, Martha M. “The Salem Witch Trials 300 Years Later: How Far Has the American Legal System Come? How Much Further Does It Need to Go?” Tulane Law Review 64 (1989): 235-258.

Mackay, Christopher S., trans. & ed. The Hammer of Witches: A Complete Translation of the Malleus Maleficarum (authored by Heinrich Institoris & Jacobus Sprenger in 1487 – Dominican friars, who were both Inquistors and professors of theology at the University of Cologne)(Cambridge University Press, BF1569.M33 2009). This medieval text (Der Hexenhammer in German) prescribes judicial procedures in cases of alleged witchcraft. In question-and-answer format. The judge should appoint as an advocate for the accused “an upright person who is not suspected of being fussy about legal niceties” as opposed to appointing “a litigious, evil-spirited person who could easily be corrupted by money” (p. 530).

“Judgment of a Witch.” The Fugger News-Letters 259-262 (The Bodley Head, Ltd., 1924). Also reprinted in The Portable Renaissance Reader.

Pagel, Scott B. The Literature of Witchcraft Trials: Books & Manuscripts from the Jacob Burns Law Library (University of Texas at Austin, BF1566.P243 2008) (Tarlton Law Library, Legal History Series, No. 9).

Witchcraft and the Law: A Selected Bibliography of Recent Publications (Christine Corcos, LSU Law)(includes mostly pre-2000 works).

1. The afflicted person makes a complaint to the Magistrate about a suspected witch. The complaint is sometimes made through a third person.

Salem Witch Trials Courtroom Photos

2. The Magistrate issues a warrant for the arrest of the accused person.

3. The accused person is taken into custody and examined by two or more Magistrates. If, after listening to testimony, the Magistrate believes that the accused person is probably guilty, the accused is sent to jail for possible reexamination and to await trial.

4. The case is presented to the Grand Jury. Depositions relating to the guilt or innocence of the accused are entered into evidence.

Salem Witch Trials Courthouse

5. If the accused is indicted by the Grand Jury, he or she is tried before the Court of Oyer and Terminer. A jury, instructed by the Court, decides the defendant's guilt.

6. The convicted defendant receives his or her sentence from the Court. In each case at Salem, the convicted defendant was sentenced to be hanged on a specified date.

7. The Sheriff and his deputies carry out the sentence of death on the specified date.